Research Trajectory

In my research I explore how systems theory and complexity theory might productively inform our research and teaching in writing and rhetoric. This work could be considered within the category of "posthuman" scholarship (a major strand of work in rhet/comp), since the systems I talk about aren't just systems of language or culture, but rather extend into the natural and material world. However, I'd argue that 1) those categories of "nature," "culture," "material," and "language" are fluid, and so there are never exclusively"human" nor "nonhuman" systems; and 2) it's important that we not lose sight of the practical implications of this work--that is, how talking about the posthuman can help us better understand our everyday human practices.

Publications

Monograph

Invisible Effects: Rethinking Writing through Emergence

Peter Lang Publishing, Studies in Composition and Rhetoric series (series editor Alice Horning)

For a shorter version of one of the arguments in this book, check out this blog post.

That link connects to a December, 2021 post I wrote for the Peter Lang Publishing blog: "What Can Complex Systems Theory Tell Us about Writing (and about Teaching Writing)?"

Invisible Effects: Rethinking Writing through Emergence

Peter Lang Publishing, Studies in Composition and Rhetoric series (series editor Alice Horning)

For a shorter version of one of the arguments in this book, check out this blog post.

That link connects to a December, 2021 post I wrote for the Peter Lang Publishing blog: "What Can Complex Systems Theory Tell Us about Writing (and about Teaching Writing)?"

Edited Collection

Kenneth Burke + The Posthuman. Ed. Chris Mays, Nathaniel A. Rivers, and Kellie Sharp-Hoskins. Penn State UP, RSA Series in Transdisciplinary Rhetoric, 2017. (Available via this link)

An excerpt from the intro:

"Posthumanism first appears as antithetical, nearly impossible, for rhetoric. In place of the polis and politics, it offers microbes and machines; instead of symbol-using animals, it foregrounds cells and cybernetics. Rhetoric concerns itself with human affairs; posthumanism seems concerned with leaving the human behind. The prospect of a posthuman rhetoric thus seems to signify, at best, a paradox, a contradiction in terms. At its worst, it suggests the end of our discipline. And yet, in the past decade as scholars (re)map and (re)imagine previously taken-for-granted categories that organize rhetorical inquiry—language, bodies, materiality, agency, responsibility, ethics—they increasingly draw on posthumanist theories to do so (Brooke 2000; Muckelbauer & Hawhee 2000; Mara & Hawk 2009; Dobrin 2015; Gries 2015; Lynch & Rivers 2015; Barnett & Boyle 2016; Boyle 2016). Posthumanism might be said to be collated by “a refusal to take humanism for granted” (Badmington 10). Rosi Braidotti explains, almost as a caveat, that “to be posthuman does not mean to be indifferent to humans, or to be de-humanized” (190). It offers, instead, both a “thematics of the decentering of the human in relation to either evolutionary, ecological, or technological coordinates” as well as an investigation into “how thinking confronts that thematics, what thought has to become in the face of those challenges” (Wolfe xvi). Posthumanism opens up the human, and it does so first and foremost by unpacking previous definitions of the human; in particular, those humanist definitions that privilege the human as some hermetically sealed, ontologically discrete entity in the world.

Perhaps the posthuman turn in rhetoric, then, spins from the propensity of posthumanist terminologies to unpack and reexamine the human. This work strikes us as rhetorical. The question of what is the rhetoric of the human moves in two compelling directions. This first, epistemological, question pursues how the concept of the human is deployed and composed as a trope. What is the history of human, how has it been employed, and to what ends? What ways of seeing and not seeing does it enable? In this posthuman move, we see a disciplinary affinity. The second, ontological, line of thought drives toward the heart of (the) matter. What is the nature of being in rhetoric? What constitutes the boundaries and features of human beings engaged in rhetoric? So much of rhetoric is predicated upon both epistemological and ontological understandings of the human. A rhetoric presumes an anthropology, so to speak. To speak of rhetoric, then, is to have already decided something about the human. We see this at work in rhetoric with none other than Kenneth Burke, whose dramatism (a way of rhetorically engaging the thorny question of motive) is paired with and grounded in his “Definition of Man.” Burke’s definition of humans as symbol-using and symbol-misuing animals is at the heart of his rhetorical project. Treating human beings as defined and distinguished as symbol-using animals sets the stage for Burke’s rhetorical project (as many of the chapters in this collection demonstrate). This grounding move, in whichever direction, inheres across rhetorical studies writ large. Burke is the figure with whom this collection engages the posthuman, which is again a renewed thinking of the human."

Table of Contents:

Articulating Ambiguous Compatibilities: An Introduction

Chris Mays, Nathaniel A. Rivers, and Kellie Sharp-Hoskins

Minding Mind: Kenneth Burke, Gregory Bateson, and Posthuman Rhetoric

Kristie S. Fleckenstein

The Cyburke Manifesto, or, Two Lessons from Burke on the Rhetoric and Ethics of Posthumanism

Jeff Pruchnic

Revision as Heresy: Posthuman Writing Systems and Kenneth Burke’s ‘Piety’

Chris Mays

Burke’s Counter-Nature: Posthumanism in the Anthropocene

Robert Wess

Technique-Technology-Transcendence: Machination and Amechania in Burke, Nietzsche, and Parmenides

Thomas Rickert

The Uses of Compulsion: Recasting Burke’s Technological Psychosis in a Comic Frame

Jodie Nicotra

A Predestination for the Posthumanistic

Steven B. Katz and Nathaniel A. Rivers

Emergent Mattering: Building Rhetorical Ethics at the Limits of the Human

Julie Jung and Kellie Sharp-Hoskins

What are Humans For?

Nathan Gale and Timothy Richardson

A Sustainable Dystopia

Casey Boyle and Steven LeMieux

Reviewed at K.B. Journal: The Journal of the Kenneth Burke Society, by David Measel.

Reviewed at Rhetoric Review, by Jason Kalin, Diane Marie Keeling, and Nathan Stormer.

Reviewed at International Journal of Communication, by Emma Frances Bloomfield.

Kenneth Burke + The Posthuman. Ed. Chris Mays, Nathaniel A. Rivers, and Kellie Sharp-Hoskins. Penn State UP, RSA Series in Transdisciplinary Rhetoric, 2017. (Available via this link)

An excerpt from the intro:

"Posthumanism first appears as antithetical, nearly impossible, for rhetoric. In place of the polis and politics, it offers microbes and machines; instead of symbol-using animals, it foregrounds cells and cybernetics. Rhetoric concerns itself with human affairs; posthumanism seems concerned with leaving the human behind. The prospect of a posthuman rhetoric thus seems to signify, at best, a paradox, a contradiction in terms. At its worst, it suggests the end of our discipline. And yet, in the past decade as scholars (re)map and (re)imagine previously taken-for-granted categories that organize rhetorical inquiry—language, bodies, materiality, agency, responsibility, ethics—they increasingly draw on posthumanist theories to do so (Brooke 2000; Muckelbauer & Hawhee 2000; Mara & Hawk 2009; Dobrin 2015; Gries 2015; Lynch & Rivers 2015; Barnett & Boyle 2016; Boyle 2016). Posthumanism might be said to be collated by “a refusal to take humanism for granted” (Badmington 10). Rosi Braidotti explains, almost as a caveat, that “to be posthuman does not mean to be indifferent to humans, or to be de-humanized” (190). It offers, instead, both a “thematics of the decentering of the human in relation to either evolutionary, ecological, or technological coordinates” as well as an investigation into “how thinking confronts that thematics, what thought has to become in the face of those challenges” (Wolfe xvi). Posthumanism opens up the human, and it does so first and foremost by unpacking previous definitions of the human; in particular, those humanist definitions that privilege the human as some hermetically sealed, ontologically discrete entity in the world.

Perhaps the posthuman turn in rhetoric, then, spins from the propensity of posthumanist terminologies to unpack and reexamine the human. This work strikes us as rhetorical. The question of what is the rhetoric of the human moves in two compelling directions. This first, epistemological, question pursues how the concept of the human is deployed and composed as a trope. What is the history of human, how has it been employed, and to what ends? What ways of seeing and not seeing does it enable? In this posthuman move, we see a disciplinary affinity. The second, ontological, line of thought drives toward the heart of (the) matter. What is the nature of being in rhetoric? What constitutes the boundaries and features of human beings engaged in rhetoric? So much of rhetoric is predicated upon both epistemological and ontological understandings of the human. A rhetoric presumes an anthropology, so to speak. To speak of rhetoric, then, is to have already decided something about the human. We see this at work in rhetoric with none other than Kenneth Burke, whose dramatism (a way of rhetorically engaging the thorny question of motive) is paired with and grounded in his “Definition of Man.” Burke’s definition of humans as symbol-using and symbol-misuing animals is at the heart of his rhetorical project. Treating human beings as defined and distinguished as symbol-using animals sets the stage for Burke’s rhetorical project (as many of the chapters in this collection demonstrate). This grounding move, in whichever direction, inheres across rhetorical studies writ large. Burke is the figure with whom this collection engages the posthuman, which is again a renewed thinking of the human."

Table of Contents:

Articulating Ambiguous Compatibilities: An Introduction

Chris Mays, Nathaniel A. Rivers, and Kellie Sharp-Hoskins

Minding Mind: Kenneth Burke, Gregory Bateson, and Posthuman Rhetoric

Kristie S. Fleckenstein

The Cyburke Manifesto, or, Two Lessons from Burke on the Rhetoric and Ethics of Posthumanism

Jeff Pruchnic

Revision as Heresy: Posthuman Writing Systems and Kenneth Burke’s ‘Piety’

Chris Mays

Burke’s Counter-Nature: Posthumanism in the Anthropocene

Robert Wess

Technique-Technology-Transcendence: Machination and Amechania in Burke, Nietzsche, and Parmenides

Thomas Rickert

The Uses of Compulsion: Recasting Burke’s Technological Psychosis in a Comic Frame

Jodie Nicotra

A Predestination for the Posthumanistic

Steven B. Katz and Nathaniel A. Rivers

Emergent Mattering: Building Rhetorical Ethics at the Limits of the Human

Julie Jung and Kellie Sharp-Hoskins

What are Humans For?

Nathan Gale and Timothy Richardson

A Sustainable Dystopia

Casey Boyle and Steven LeMieux

Reviewed at K.B. Journal: The Journal of the Kenneth Burke Society, by David Measel.

Reviewed at Rhetoric Review, by Jason Kalin, Diane Marie Keeling, and Nathan Stormer.

Reviewed at International Journal of Communication, by Emma Frances Bloomfield.

Peer-reviewed Articles

"More Complexity, Less Uncertainty: Changing How We Talk (and Think) about Science." Electronic Journal for Research in Science and Mathematics Education, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2023. (Special Call: Critical Rhetoric in Science and Mathematics Education)

Abstract: This article focuses on the phenomenon of complexity in scientific communication. The article argues that shifting frames in science communication and the rhetoric of science from uncertainty to complexity can benefit audience understanding of scientific issues, and can also prevent bad-faith uptake of these issues that can be used to stoke political divisions. Such detrimental uptake happened with several science communication issues related to the Covid-19 pandemic. The rhetorical strategy detailed here balances the need to support mainstream science while also incorporating some critique of it. Such a balance can be beneficial for the ethos of scientists and science communicators, and can result in more robust public engagement.

"Ignorance as a Productive Response to Epistemic Perturbations."

Synthese, Vol. 198, 2021, pp. 6491–6507. (Special Issue: "Knowing the Unknown")

It would seem a safe statement to say that ignorance is bad, or is a thing to be avoided, or that we know more now than we did when we were young children. However, this article argues precisely that this is not the case. Not only is ignorance a form of epistemic management, but also, there are no absolute “facts” to know or not to know, and so ignorance is neither good nor bad, and there is no context-free sense of knowing more and being less ignorant. Ignorance and knowledge, then, are not inversely proportional, and having knowledge does not function to decrease ignorance:

"As this paper argues, ignorance is productive, in that it produces new knowledge that works to make rhetoric systems more resistant to potential destabilization. To elaborate these points, the paper examines discourse about the phenomenon of global climate change, which illustrates how individuals productively counter information as a way of preserving beliefs."

Image credit: https://www.maxpixel.net/ (foreground) and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Star#/media/File:Pleiades_large.jpg (background). License: CC0 (foreground) and public domain (background)

"Learning from Interdisciplinary Interactions: An Argument for Rhetorical Deliberation as a Framework for WID Faculty." (co-authored with Maureen N. Mcbride) Composition Forum, Vol. 43, Spring 2020.

"As we are proposing in this article, a systemic model of [WAC/WID] collaboration that treats cross-disciplinary negotiations as a rhetorical deliberation that involves both collaborative and adversarial interactions is a viable approach for these situations and provides a framework that writing faculty can use to help guide them through this complex process. . . . Overall, the point in using [an] adversarial deliberative model is not to feature exclusively a negative, combative version of conflict. The point, rather, is to understand the approach to interaction as strategic, and to understand the interaction itself as not only a collaboration, but also as an argument between those with fundamentally different and perhaps even competing interests."

Image credit: Vikramdeep Sidhu https://www.flickr.com/photos/deep_sidhu/41506115794. License: CC Attribution 4.0 International

"'You Can’t Make This Stuff Up': Complexity, Facts, and Creative Nonfiction." College English, vol. 80, no. 4, 2018, pp. 319-41.

"As this article argues, the primary source of writing’s power is not its simplicity, but rather its ability to disguise its own incredible complexity. . . . To explain this idea, this article zeroes in on a controversy over “facts” that exposes the problems that arise when writing’s complexity is overlooked. To some extent, this is a recapturing of the root of the word “fact” itself—the Latin term facere: to make, or to do. The making of facts is exactly what is at issue here, as the aim is to explore the complex ways facts are made, rather than assuming them to be already finished building blocks of a universal and static reality. More specifically, this article explores the debate over the fabrication of details in what Bronwyn T. Williams calls “the amorphous realm” of “creative nonfiction.” . . . What this article proposes is that, given the complexity of the questions and debates involving fact, fiction, and truth in nonfiction writing, exposing the complex functioning of writing specifically in this genre advances our understanding of how all writing works on audiences, and, how writing genres—and facts overall—are divergently perceived."

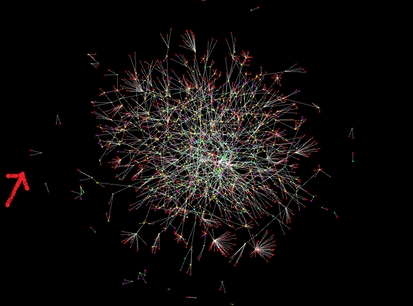

"Writing Complexity, One Stability at a Time: Teaching Writing as a Complex System." College Composition and Communication, vol. 68, no. 3, 2017, pp. 559-85.

"It is no exaggeration, nor is it a metaphor, to say that writing can be considered a complex system. This is precisely the promise of systems theory: to map out the ways that different complex phenomena cohere as self-sustaining entities within a similarly complex environment. And surely, writing is complex, has interacting elements, and coheres in contexts that also are vastly complex. . . . When we theorize writing in this way, we can see a single text, for example, as an instantiation of self-organization in the larger complex system of writing. In other words, writing is self-organized, just as are other systems, but just as with other systems we only perceive this order by freezing the writing system in a stable configuration: in this case, by making the cut in our observations and drawing boundaries to define a static text. As such a self-organized moment, a text exists as a stability that is constantly being negotiated—neither messily indeterminate nor in an unpredictable flux, a text is in fact perceived as stable in a “cut” that is a contingently frozen snapshot of our apprehension of writing."

* Link to CCC podcast about this article.

Image credit: Simon Cockell https://www.flickr.com/photos/sjcockell/3251147920/ (CC 2.0)

"It is no exaggeration, nor is it a metaphor, to say that writing can be considered a complex system. This is precisely the promise of systems theory: to map out the ways that different complex phenomena cohere as self-sustaining entities within a similarly complex environment. And surely, writing is complex, has interacting elements, and coheres in contexts that also are vastly complex. . . . When we theorize writing in this way, we can see a single text, for example, as an instantiation of self-organization in the larger complex system of writing. In other words, writing is self-organized, just as are other systems, but just as with other systems we only perceive this order by freezing the writing system in a stable configuration: in this case, by making the cut in our observations and drawing boundaries to define a static text. As such a self-organized moment, a text exists as a stability that is constantly being negotiated—neither messily indeterminate nor in an unpredictable flux, a text is in fact perceived as stable in a “cut” that is a contingently frozen snapshot of our apprehension of writing."

* Link to CCC podcast about this article.

Image credit: Simon Cockell https://www.flickr.com/photos/sjcockell/3251147920/ (CC 2.0)

"From 'Flows' to 'Excess': On Stability, Stubbornness, and Blockage in Rhetorical Ecologies." enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, vol. 19, 2015.

In this article, using key concepts taken from theories of complex systems—many of the very same theories in which rhetorical ecological approaches are themselves rooted—I examine apparently static rhetorical ecologies, as well as aspects of all rhetorical ecologies that would seem inhibitive to the flows (and rhetorical effects of these flows) that constitute a vibrant ecosystem. In so doing, I productively complicate the relationship of movement and stability. Crucially, I argue that thinking of a rhetorical ecology in terms of “excess” can help us better understand the way flows and evolution work in relation to the seemingly opposed ideas of blockage and stubbornness. While these latter terms would seem to point to a lack of movement—and a correspondent lack of rhetorical effects present—in an ecology, paradoxically, I argue the very presence of such stability is evidence of movement and rhetorical effects. In short, what I call a “rhetoric-systems” approach gives us an account of stability that highlights both its necessity and its productive role in a rhetorical ecology. . . . In my analysis I describe how seemingly stubborn beliefs often thrive as part of what I call a rhetoric system (a term meant to evoke the systems described in complex systems theory, much of which does not rely on the term “ecology”). In such a rhetoric system, a wide variety of beliefs can persist in the face of what might appear to be irrefutable contrary evidence. As I will show, while persistence of belief may seem to indicate an ecology closed to evolution and lacking in rhetorical effect, in fact this tenacity indicates just the opposite, and it is a key feature of all rhetoric systems. This means that what are often considered stubborn beliefs, rather than an exclusive feature of one particular ideology or political party, are an integral and complex part of the way knowledge is created, sustained, and circulated in a rhetorical ecology.

Image credit: http://enculturation.net/19

In this article, using key concepts taken from theories of complex systems—many of the very same theories in which rhetorical ecological approaches are themselves rooted—I examine apparently static rhetorical ecologies, as well as aspects of all rhetorical ecologies that would seem inhibitive to the flows (and rhetorical effects of these flows) that constitute a vibrant ecosystem. In so doing, I productively complicate the relationship of movement and stability. Crucially, I argue that thinking of a rhetorical ecology in terms of “excess” can help us better understand the way flows and evolution work in relation to the seemingly opposed ideas of blockage and stubbornness. While these latter terms would seem to point to a lack of movement—and a correspondent lack of rhetorical effects present—in an ecology, paradoxically, I argue the very presence of such stability is evidence of movement and rhetorical effects. In short, what I call a “rhetoric-systems” approach gives us an account of stability that highlights both its necessity and its productive role in a rhetorical ecology. . . . In my analysis I describe how seemingly stubborn beliefs often thrive as part of what I call a rhetoric system (a term meant to evoke the systems described in complex systems theory, much of which does not rely on the term “ecology”). In such a rhetoric system, a wide variety of beliefs can persist in the face of what might appear to be irrefutable contrary evidence. As I will show, while persistence of belief may seem to indicate an ecology closed to evolution and lacking in rhetorical effect, in fact this tenacity indicates just the opposite, and it is a key feature of all rhetoric systems. This means that what are often considered stubborn beliefs, rather than an exclusive feature of one particular ideology or political party, are an integral and complex part of the way knowledge is created, sustained, and circulated in a rhetorical ecology.

Image credit: http://enculturation.net/19

“Priming Terministic Inquiry: Toward a Methodology of Neurorhetoric.” (co-authored with Julie Jung) Rhetoric Review, vol. 31, no. 1, 2012, pp. 41–59.

Integral to the neurorhetorical methodology we propose is a critical exchange of research between fields, one that not only explores how research in brain science can contribute to work in rhetoric-composition but also submits this appropriated research to the same critical inquiry and informed debate so productive in our own discipline. . . . When dealing with a discourse as appealing as brain science, those of us interested in cross-disciplinary reciprocity need a rhetoric that reminds us how much we don’t know about how the brain “really” works. Neurorhetoric provides this reminder because it consciously attends to the ways in which shared terminology can induce readers to mistake arguments for empirical proofs. Without this reminder teacher-scholars in the field risk reifying every new neuroscientific theory that gains ascendance. More crucially, however, when we who are trained in rhetoric fail to analyze brain research rhetorically, we abdicate our responsibility to influence and complicate its uptake in broader publics, such as boards of regents, college administrators, and university curriculum committees. In short, ours is a methodology intended to help rhetoric-compositionists intervene productively in simplistic conversations about brain research that are now or soon will be taking place within and beyond the field.

Integral to the neurorhetorical methodology we propose is a critical exchange of research between fields, one that not only explores how research in brain science can contribute to work in rhetoric-composition but also submits this appropriated research to the same critical inquiry and informed debate so productive in our own discipline. . . . When dealing with a discourse as appealing as brain science, those of us interested in cross-disciplinary reciprocity need a rhetoric that reminds us how much we don’t know about how the brain “really” works. Neurorhetoric provides this reminder because it consciously attends to the ways in which shared terminology can induce readers to mistake arguments for empirical proofs. Without this reminder teacher-scholars in the field risk reifying every new neuroscientific theory that gains ascendance. More crucially, however, when we who are trained in rhetoric fail to analyze brain research rhetorically, we abdicate our responsibility to influence and complicate its uptake in broader publics, such as boards of regents, college administrators, and university curriculum committees. In short, ours is a methodology intended to help rhetoric-compositionists intervene productively in simplistic conversations about brain research that are now or soon will be taking place within and beyond the field.

Book Chapters

"Articulating Ambiguous Compatibilities: An Introduction." Co-authored with Nathaniel A. Rivers and Kellie Sharp-Hoskins. In Kenneth Burke + The Posthuman.

(see above)

"Revision as Heresy: Writing Systems and Kenneth Burke's 'Piety.'" In Kenneth Burke + The Posthuman.

By taking seriously the notion that texts themselves can have agency, this chapter complicates commonplace notions of writing and, in particular, of revision. While commonplaces of revision link it to writing, and to rewriting, explicating the concept in terms of complex systems theory reveals that there is more to revision than the dutiful and linear reworkings of a creator on her creation, ever striving toward a singular perfection devoid of “mistakes.” . . . Here, Burke's piety becomes an indispensable complement to our understanding of revision by casting revision simultaneously as a deeply personal process that inspires intense feelings of ownership as well as an impersonal function of a complex system neither owned nor created by any one person or agency.

"Wild Meaning: The Intercorporeal Nature of Objects, Bodies, and Words." Co-authored with J. Scott Jordan. In Intercorporeality: Emerging Socialities in Interaction. Ed Christian Meyer, Jürgen Streeck, and J. Scott Jordan. Oxford UP, 2017.

This chapter explores "wild systems theory" (WST), a version of systems theory that emphasizes a system's quality of being "about" its context. On this view, the work that goes on within the systems produces products (e.g., ideas and shared ideas) that give rise to outcomes that sustain the work. As an example, sustaining and perpetuating a belief in socialism, or capitalism, constrains one’s way of being in the world in ways that give rise to products that feed into and sustain the existence of socialism and capitalism which, in turns, feeds into and sustains one’s belief. To a person enmeshed within in a particular rhetoric system, his or her understanding of events, texts, and specific words will seem static, and the total holistic understanding of those static meanings will be internally coherent. In rhetoric systems, as is the case with all self-sustaining systems, the relations that constitute the system will be constrained by the other rhetorical systems with which it is in relation. That is, the rhetorical system will embody its context. Such an approach to language and rhetorical systems transcends subject-object divides and provides a way of conceptualizing language that makes it much more consistent with WST’s notion of embodied context, and Merleau-Ponty’s notion of intercorporeity.

Conference Proceedings

"CCID: Articulating a Design-Thinking Center for Multimodal Communication." Co-authored with William Macauley and Katherine J. Hepworth. In Proceedings of the 34th ACM International Conference on the Design of Communication. Association for Computing Machinery, 2016.

In higher education institutions, writing in the disciplines (WID) and writing across the curriculum (WAC) programs are commonly received reluctantly by other disciplines and programs (Perelman). The context for these programs - servicing schools and departments but remaining apart from them - creates problems for facilitating effective service. At the University of Nevada, Reno, a new program began in 2015, called Composition and Communication in the Disciplines (CCID) and focusing on building student writing, presenting, and multimodal communication. To counter disciplinary reticence about such programs, CCID uses design thinking at its relational heuristic. In this context, design thinking serves as a means to engage with diverse disciplines and modes of communication active on campus while avoiding the perception of imposed disciplinarity. Although a number of scholars have written about the parallels between design and writing (Purdy; Norman), design thinking has yet to be used as part of a writing program in this way. Here, we give a short overview of CCID, followed by details of how and why this design thinking-based, multimodal communication program is developing.

Invited Response Essay

“Who’s Driving this Thing, Anyway?: Emotion and Language in Rhetoric and Neuroscience.” JAC: A Journal of Cultural Theory, vol. 33, no. 1–2, 2013. (full text via Academia.edu)

As social psychologists Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson extensively document, people habitually and nonconsciously “self-justif[y]” in order to reduce the “pangs” or “anguish” caused by an encounter with an idea or piece of evidence that contrasts with one of their beliefs (13). And as Martha Nussbaum writes in Hiding from Humanity, we are compelled to reject people and ideas that make us feel “inadequate, lacking some desired type of completeness or perfection” (184). We shirk, in other words, from things that make us feel or seem vulnerable and incomplete, and we rationalize or “deflect” in order to revise our emotional responses—often in such a way that is favorable to our own views. But this “art of deflection par excellence,” as Lynn Worsham refers to it (414), is rhetoric. And as language use is unavoidably tied up with how we respond to our emotions, how we re-present (in language) our bodies’ emotions radically influences their very makeup.

Book Review

Review of The Neuroscientific Turn: Transdisciplinarity in the Age of the Brain (Ed. Melissa Littlefield and Jenell Johnson. Ann Arbor: U Michigan P, 2013.) Reviewed in IMPACT: The Journal of the Center for Interdisciplinary Teaching and Learning, vol. 3, no. 2, 2014.

Dissertation

Building Complexity, One Stability at a Time: Rethinking Stubbornness in Public Rhetorics and Writing Studies

"Articulating Ambiguous Compatibilities: An Introduction." Co-authored with Nathaniel A. Rivers and Kellie Sharp-Hoskins. In Kenneth Burke + The Posthuman.

(see above)

"Revision as Heresy: Writing Systems and Kenneth Burke's 'Piety.'" In Kenneth Burke + The Posthuman.

By taking seriously the notion that texts themselves can have agency, this chapter complicates commonplace notions of writing and, in particular, of revision. While commonplaces of revision link it to writing, and to rewriting, explicating the concept in terms of complex systems theory reveals that there is more to revision than the dutiful and linear reworkings of a creator on her creation, ever striving toward a singular perfection devoid of “mistakes.” . . . Here, Burke's piety becomes an indispensable complement to our understanding of revision by casting revision simultaneously as a deeply personal process that inspires intense feelings of ownership as well as an impersonal function of a complex system neither owned nor created by any one person or agency.

"Wild Meaning: The Intercorporeal Nature of Objects, Bodies, and Words." Co-authored with J. Scott Jordan. In Intercorporeality: Emerging Socialities in Interaction. Ed Christian Meyer, Jürgen Streeck, and J. Scott Jordan. Oxford UP, 2017.

This chapter explores "wild systems theory" (WST), a version of systems theory that emphasizes a system's quality of being "about" its context. On this view, the work that goes on within the systems produces products (e.g., ideas and shared ideas) that give rise to outcomes that sustain the work. As an example, sustaining and perpetuating a belief in socialism, or capitalism, constrains one’s way of being in the world in ways that give rise to products that feed into and sustain the existence of socialism and capitalism which, in turns, feeds into and sustains one’s belief. To a person enmeshed within in a particular rhetoric system, his or her understanding of events, texts, and specific words will seem static, and the total holistic understanding of those static meanings will be internally coherent. In rhetoric systems, as is the case with all self-sustaining systems, the relations that constitute the system will be constrained by the other rhetorical systems with which it is in relation. That is, the rhetorical system will embody its context. Such an approach to language and rhetorical systems transcends subject-object divides and provides a way of conceptualizing language that makes it much more consistent with WST’s notion of embodied context, and Merleau-Ponty’s notion of intercorporeity.

Conference Proceedings

"CCID: Articulating a Design-Thinking Center for Multimodal Communication." Co-authored with William Macauley and Katherine J. Hepworth. In Proceedings of the 34th ACM International Conference on the Design of Communication. Association for Computing Machinery, 2016.

In higher education institutions, writing in the disciplines (WID) and writing across the curriculum (WAC) programs are commonly received reluctantly by other disciplines and programs (Perelman). The context for these programs - servicing schools and departments but remaining apart from them - creates problems for facilitating effective service. At the University of Nevada, Reno, a new program began in 2015, called Composition and Communication in the Disciplines (CCID) and focusing on building student writing, presenting, and multimodal communication. To counter disciplinary reticence about such programs, CCID uses design thinking at its relational heuristic. In this context, design thinking serves as a means to engage with diverse disciplines and modes of communication active on campus while avoiding the perception of imposed disciplinarity. Although a number of scholars have written about the parallels between design and writing (Purdy; Norman), design thinking has yet to be used as part of a writing program in this way. Here, we give a short overview of CCID, followed by details of how and why this design thinking-based, multimodal communication program is developing.

Invited Response Essay

“Who’s Driving this Thing, Anyway?: Emotion and Language in Rhetoric and Neuroscience.” JAC: A Journal of Cultural Theory, vol. 33, no. 1–2, 2013. (full text via Academia.edu)

As social psychologists Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson extensively document, people habitually and nonconsciously “self-justif[y]” in order to reduce the “pangs” or “anguish” caused by an encounter with an idea or piece of evidence that contrasts with one of their beliefs (13). And as Martha Nussbaum writes in Hiding from Humanity, we are compelled to reject people and ideas that make us feel “inadequate, lacking some desired type of completeness or perfection” (184). We shirk, in other words, from things that make us feel or seem vulnerable and incomplete, and we rationalize or “deflect” in order to revise our emotional responses—often in such a way that is favorable to our own views. But this “art of deflection par excellence,” as Lynn Worsham refers to it (414), is rhetoric. And as language use is unavoidably tied up with how we respond to our emotions, how we re-present (in language) our bodies’ emotions radically influences their very makeup.

Book Review

Review of The Neuroscientific Turn: Transdisciplinarity in the Age of the Brain (Ed. Melissa Littlefield and Jenell Johnson. Ann Arbor: U Michigan P, 2013.) Reviewed in IMPACT: The Journal of the Center for Interdisciplinary Teaching and Learning, vol. 3, no. 2, 2014.

Dissertation

Building Complexity, One Stability at a Time: Rethinking Stubbornness in Public Rhetorics and Writing Studies